Here They Go Again: The Democratic Obsession with Drug Price Controls Will Harm Patients and Diminish Innovation

The U.S. House of Representatives is once again considering “The Lower Drug Costs Now Act”. It was a bad idea in the last Congress, and it is still bad policy today.

If it becomes law, this Act (H.R. 3) empowers the federal government to negotiate prices on select drugs for the entire country. By statute, the government will base the negotiations on the prices charged in other nations. Since these nations impose stringent price controls on drugs, H.R. 3 is a means to implement drug price controls in the U.S. without having to explicitly defend the policy.

Politically, this makes sense because price controls never achieve their lofty goals and will create significant economic harm. In fact, this is precisely what the government’s own analyses found when evaluating the exact same policy last year.

According to the Council of Economic Advisers (CEA), this act

could lead to as many as 100 fewer drugs entering the United States market over the next decade, or about one-third of the total number of drugs expected to enter the market during that time. CEA also estimates that by limiting access to lifesaving drugs, H.R. 3 would reduce Americans’ average life expectancy by about four months—nearly one-quarter of the projected gains in life expectancy over the next decade.

An analysis by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) came to a similar conclusion. The CBO estimated that reference pricing could reduce drug industry revenues by up to $1 trillion over 10 years. Drug companies devote about 20 percent of their revenues to R&D, which indicates that any reference pricing scheme would shortchange R&D by hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade. Thus, the CBO also concludes that there would be significantly fewer drugs developed over the next 10 years should a reference pricing scheme become effective.

These analyses confirm the expectation that the reference pricing proposal contained in the Lower Drug Costs Now Act will reduce innovation and harm patients. Unfortunately, there are more harmful provisions in this Act.

For instance, the Act would impose a penalty on drug manufacturers if the price of a drug increases faster than inflation. When prices rise faster than inflation, drug manufacturers would be forced to pay rebates back to the federal government.

There is no reason why the prices of drugs should increase at the same rate as the prices of houses, cars, or food in any given year. In some years drug prices may be expected to rise faster, but in other years drug prices should be expected to rise slower than overall inflation. In fact, prices for brand-name drugs have been growing slower than inflation over the past four years.

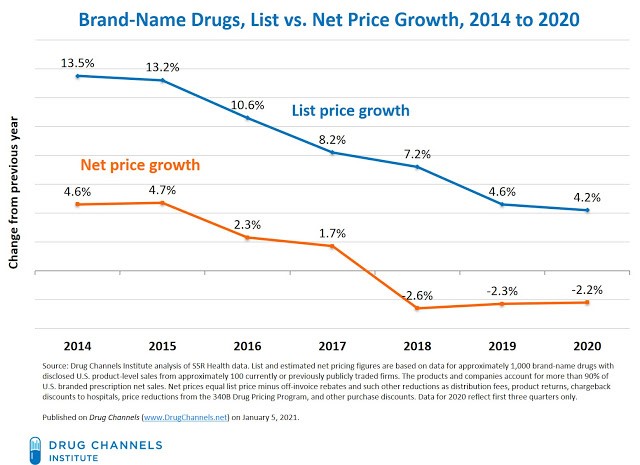

According to a January 5, 2021 Drug Channels Institute analysis, prices for brand-name drugs (properly measured) grew 1.7 percent in 2017, and then declined in 2018 through 2020. The caveat “properly measured prices” is important. The list price for drugs is often used as a measure of a drug’s price, but the list price excludes the hundreds of billions of dollars in discounts and other concessions manufacturers pay insurers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). The net price accounts for these discounts and, consequently, accurately measures how much the healthcare system is paying for drugs.

The orange line in the below figure, copied from the Drug Channels Institute, tracks the percentage change in prices accounting for all of these concessions. Inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index grew 2.1 percent, 2.4 percent, 1.8 percent, and 1.2 percent, respectively, over the same time period. Consequently, the prices for brand-name drugs have been growing slower than inflation for many years now.

Since the Lower Drug Cost Now Act would punish drug companies when drug prices exceed inflation in a given year, but would not reward them when they increase at a lesser rate, it discourages manufacturers from holding price increases below the rate of inflation as they have over the past four years. Consequently, this provision of the Act will incent higher initial prices and, ironically, faster growing net prices for medicines compared to recent trends.

Taken together, the provisions of the Lower Drug Costs Now Act will worsen the healthcare system.

The inflation penalty would all but ensures that prices will continually rise each and every year if enacted. The price controls would threaten continued innovation, which could delay or perhaps derail potential treatments for Alzheimer’s Disease, cancer, or muscular dystrophy. The less innovative environment the act would usher in would also lessen the ability of the industry to effectively respond to the next global pandemic. These losses would impose substantial costs on the economy and will significantly reduce the wellbeing of patients, who will likely suffer the most.

Dr. Wayne Winegarden is the director of the Center for Medical Economics and Innovation at the Pacific Research Institute, and is a PRI senior fellow in business and economics.